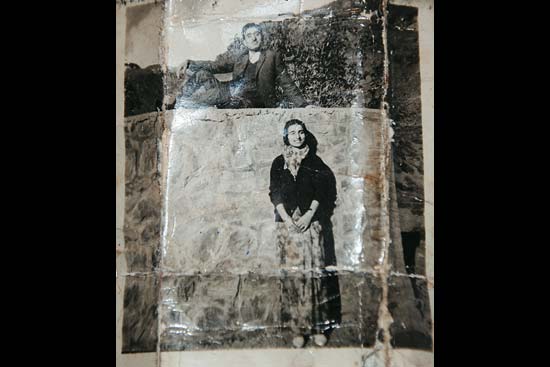

Twenty-five years into exile, a Pandit selects memory props to remind him like shrapnel pain of the day his family looked its last upon Kashmir Valley

I often think of a man I saw dead 30 years ago in Srinagar on the road outside the Silk Factory. The man had died after being hit by a truck; he lay face down, and the pieces of meat he was carrying in a newspaper sheet lay strewn all over him. The bus from which I saw him stopped for a moment and I remember trying to read the crumpled and stained newspaper. I wanted to read the printed matter so that it could serve as a prop to remember the dead man.

I always needed a prop to remember things by. Six years after I saw that dead man, I was in a taxi, huddled with my parents, who like every Kashmiri Pandit at that time were desperate to see the light on the other end of the Jawahar tunnel. While crossing south Kashmir, we came across a man pushing a wheelbarrow on the road; he looked at us in disgust, pumped his fist in the air, and shouted: “

Maryu, Batav, maryu! (Die, you Pandits, die!).” The man’s wheelbarrow and his raised fist are among the many props reminding me of my exile.

Anniversaries are also like props. January 19 this year, for example, will mark 25 years of our exodus from the Kashmir Valley. I don’t know whether this date means something to my father. I don’t think he will even remember it. His day will be the same: he will wake up, worry about what we will cook for lunch, ask me with remarkable sangfroid if I have plans to get married, recite mantras in front of a picture of our ancestral goddess. Later, he will ring up the grocer to order something, beginning with: “Hello, Mintuji,

mein Uncle bol raha hun!” and then place his order. Earlier, I’d find it funny, since I thought Mintu must be dealing with 50 uncles like Father. But then I paid attention and realised Mintu never asks: “Which uncle?” The system worked perfectly for Father, the groceries always got delivered on time. That is how he operated back home in Kashmir; that is how it works for him in Gurgaon.

But I know Father misses home. We never talk about it. Not even when he is watching DD Kashmir, when he is humming along with Tibet Bakal singing a

Krishan Joo Razdan Leela, an ode to Shiva. Father has never returned to Kashmir since April 4, 1990. I don’t think he wants to. The Kashmir he left 25 years ago has changed. And he remembers every moment of the time that change occurred. So January 19, in his mind, is no different from all those days of fear and trauma in 1989-90. As Robert Frank writes in

La memoire des Francais, “That which is sadly memorable is not co-memorable.”

Somehow, in my head—and perhaps that is the way it is with every son and daughter—Father has always been ‘old’. But how old was he when we left home? He was 44. Forty-four! At that age, like thousands of other Kashmiri Pandit parents, he had to provide for the family in so uncertain times. At that age, he lost everything he had so lovingly built along with my mother: a home, its red-cemented corridor, its lawn, its kitchen garden, its windows with stained glass, its wardrobes, its false ceiling, its book-shelves. Everything my parents earned for years was diligently put into our home. And, suddenly, one day, your neighbours, your colleagues, your friends, your grocer and your milkman decide that you cannot live in a home that you built with your sweat and blood. They also decide that it is time for you to leave not only your home, but also the land where your ancestors lived for thousands of years. So they burst out on the streets on the night of January 19, 1990, and shout on loudspeakers from the mosques all over the Valley that they want Kashmir to become Pakistan, where only Pandit women (and no men) will be allowed.

Oh, that night! How can I forget it! How can any Kashmiri Pandit forget it! But I am still searching for more and more props to remember that night. I want it to be like shrapnel pain. Here is one prop I acquired recently: on that night Doordarshan was playing a V. Shantaram film,

Teen Batti, Chaar Raasta. Also, that night, along with frenzied cries for our annihilation, they played a song used in Afghanistan to inspire the anti-Soviet militia:

Khoon-e-shahidan rang laaya, fatah ka parcham lehraya, jaago jaago subah hui (The blood of the martyrs has come true, the flag of victory has been unfurled, wake up, wake up, he dawn has appeared). It is now available on YouTube and, sometimes, when a few friends get silly drunk, we play it on and laugh as we imitate the singer’s nasal drone. This is what I believe Michael Taussig called the “normality of the abnormal” in

Nervous System, when he referred to the notion of “despair and macabre humour”.

But I cannot play the song when Father is around. I cannot play it to a man who spent that entire night standing at his window, offering the solace of his presence to an old woman who was alone in the neighbouring house, as mobs outside were calling for the death of Pandits. I cannot play it to a woman, then a child, whose mouth was stuffed with Parle-G biscuits by her mother to prevent her from crying and attracting the attention of the mob outside her home. I cannot play it to the widow of Naveen Sapru, who at the age of 37 was waylaid by a mob outside a mosque and then shot. “

Bus, be moodus wanye (Okay, I have died now),” he told his murderers, after which he was shot again and silenced forever. Naveen was on his way to collect his coat from a tailor. But he was killed before that. Two years ago, while in the US, I bought a coat from Macy’s and it reminded me of him.

Did anyone collect his coat later?

Twenty-five years is a long time. For a refugee, it indicates a sense of permanent exile. In exile, most of us are doing well for ourselves. But beneath our tiepins, our PowerPoint presentations, our single malts, our Harvard ‘five-foot shelf’ classics, we suffer from an acute sense of homelessness. In exile, our achievements are like pieces of meat over that man’s dead body. In exile, we are like Orwell’s Unhappy Bella, waiting for unknown fishermen to sing the sad song of our betrayal.

We wait for the spring. But on January 19, twenty-five years later, the exile is winter. A mind of winter, as Wallace Stevens would have preferred to call it.

(Rahul Pandita is the author of Our Moon Has Blood Clots (2013), a memoir of exile from Kashmir.)

No comments:

Post a Comment